Mondrian Before Abstraction

Decades before becoming New York’s Pied Piper for nonobjective art, Piet Mondrian had established a reputation in Europe for navigating and remaking realism in his own image.

Piet Mondrian, “Windmill in Twilight” (c. 1907-1908), oil on canvas, 67.5 x 117.5 cm; © Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Netherlands (all images courtesy Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris)

PARIS — Reliable histories about postwar abstraction in New York always include the pivotal role played by Dutch émigré Piet Mondrian. He lived there for only the last four years of his life but had an outsized influence on the American scene.

Kingmaker Peggy Guggenheim awaited Mondrian’s endorsement of Jackson Pollock before including the latter in a show of new American painting. Fellow Dutch immigrant Willem de Kooning is said to have advised young downtown artists to keep Mondrian in their back pocket like a compass. When Mondrian died, about 200 artists attended his New York funeral.

Decades before becoming New York’s Pied Piper for nonobjective art, he had established a reputation in Europe for navigating and remaking realism in his own image. The Figurative Mondrian at Musée Marmottan Monet features 70 paintings and drawings from more than 180 Mondrians held in the estate of his early collector, fellow Dutchman Salomon Slijper, whose financial support freed the young artist to leave Holland for a brief engagement with the bustling art scene in Paris.

Influenced by that milieu, Mondrian graduated into deepening experiments with abstraction, a turn that would, ironically, end Slijper’s prescient investment in the artist. Though the Slijper-Mondrian relationship provides a unifying thread for this exhibition, it’s the artist’s surprising reinvention of realism that provides the engine for its narrative.

Piet Mondrian, “House” (1898-1900), watercolor and gouache and opaque white on paper, 45.6 x 58.4 cm; © Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Netherlands

The artist’s biography spans the trajectory of Modernism. As scholar Hans Janssen notes in the exhibition’s catalog, the aging artist died “under fluorescent lights high up in a skyscraper in Manhattan,” in 1944, but he was born in 1872 by candlelight in the medieval Dutch town of Amersfoort. The young Mondrian attended the Rijksakademie van beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, and the initial paintings collected by Slijper reflect that traditional schooling. “Dead Hare” (1891), which kicks off the show with its suffused light and arresting, naturalistic detail, could be the handiwork of a Dutch forebear like Pieter van Noort.

Young Mondrian found his voice as a landscape painter, venerating the natural world while altering its tone, mood and texture. A standout is “House” (1889-1900) which synthesizes academic realism with an incipient Impressionism. Blue-green washes in gouache and watercolor depict a garden teeming with spiky, trellised flowers and whorling tree branches. In the distance, cattle graze on sea-colored pastureland underneath a speckled, radiant sky. The fluidity of the landscape’s natural beauty provides a distinct foil to the angular heft of the gray, wedge-shaped clapboard house that dominates the picture plane.

Another striking development is the artist’s judicious romanticism, as the landscapes track fluctuating light in sequential hours of the day and across varied seasons. Some landscapes explore cloud-covered gloom, like “Landscape with Trees Along the Gein” (1907) in which the river mirrors stark woodlands. Smaller landscapes like “Geinrust Farm in the Haze” (1906-7) rely on rapid, thick brushstrokes to suggest a world materializing at dawn.

Piet Mondrian, “Large Landscape” (c.1907-1908), oil on canvas, 75 x 120 cm; © Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Netherlands

Other landscapes study nature’s expansiveness along wooded pathways or across open fields, as sunlight ebbs and encroaching shadows turn wooden barns and wind-tossed grasslands into silhouettes. Windmills, as stand-ins for human activity, absorb and reflect Mondrian’s masterful light – sometimes glowing red in direct sunlight, and other times cloaked in shade near sundown. Tall, tapered trees loom like sentinels, asserting nature’s gentle authority. It is in the trees that we sometimes detect interlacing networks that begin to stand apart from the overall composition, hinting at the radical abstractions to come.

Mondrian’s developing interest in peeling back nature’s outward appearance to reveal its hidden forms coincides with his aesthetic self-education, which is mapped out chronologically on the galleries’ wall plates. It’s uncertain whether the artist’s visit to a Van Gogh exhibition in Amsterdam in 1905 had a transformational effect or remained an ephemeral inspiration. But there is little doubt that Vincent’s example played a part in Mondrian’s startling if short-lived turn to thick brushwork and high-keyed color. The fiery yellow and red “Mill in Sunlight” (1908) marks a complete departure from his prior, more naturalistic landscapes. Here, a relentless sun inundates the mill, seeming to set its exoskeleton ablaze in pulsating reds and oranges.

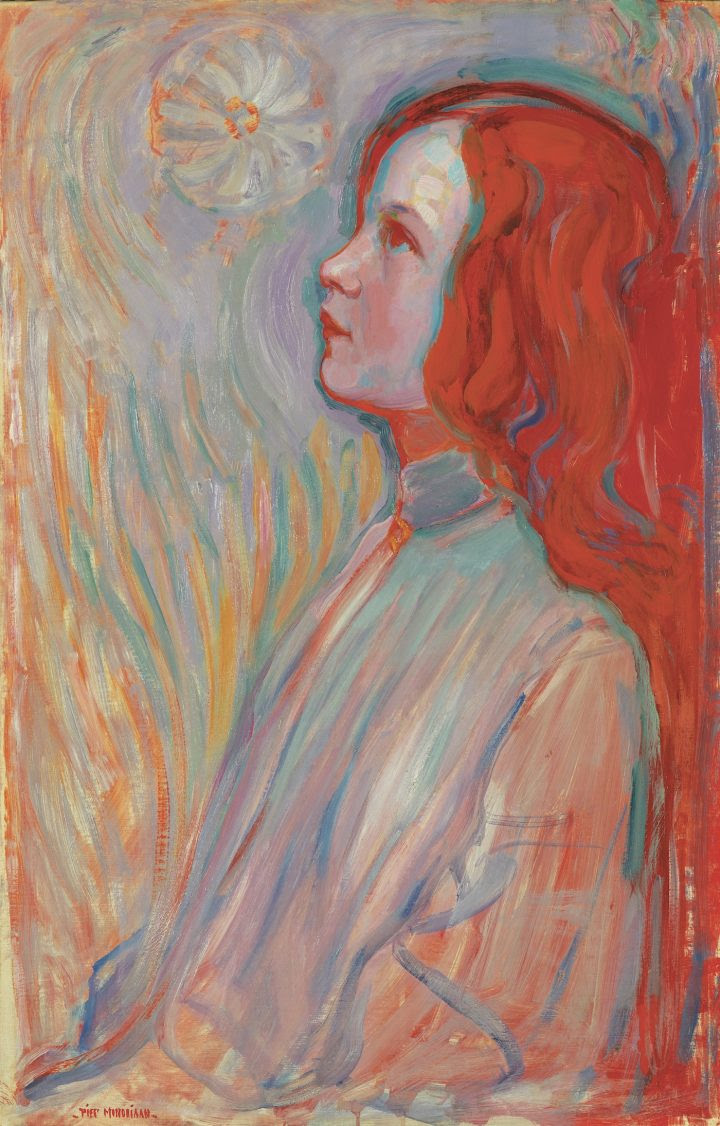

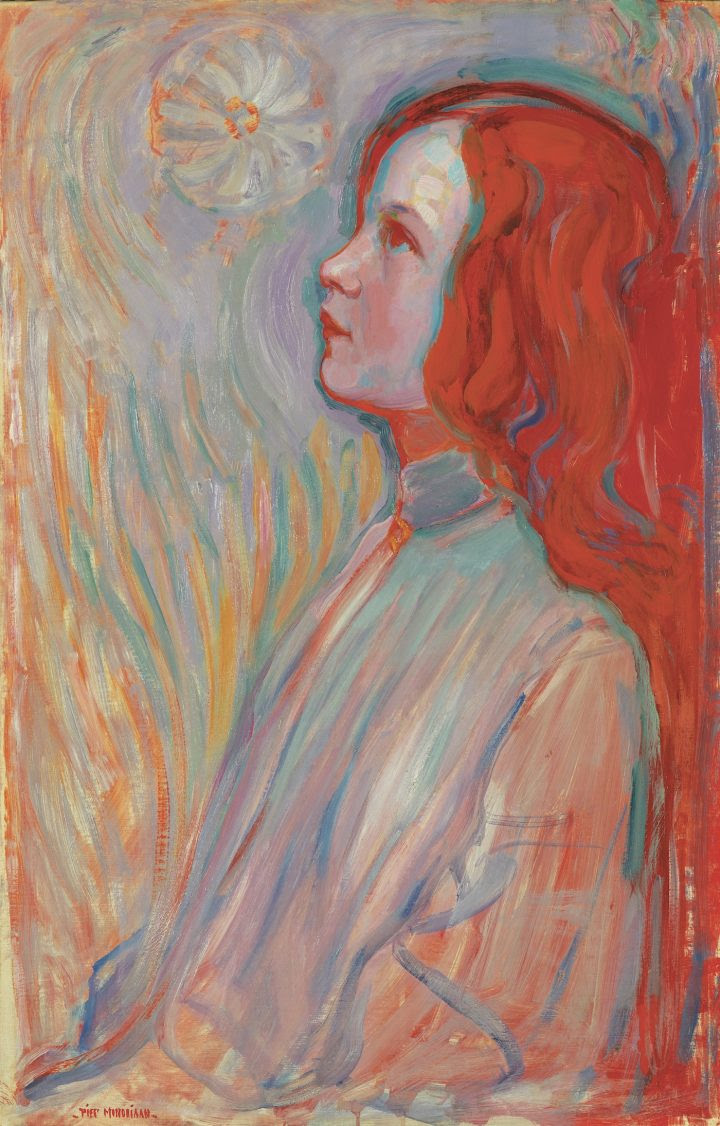

Piet Mondrian, “Devotion” (1908), oil on canvas, 94 x 61 cm; © Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Netherlands

Around this time, Fauvist-inspired portraits begin to appear, dominating the exhibition’s midpoint as the usually restrained artist dials up the chromatic heat to a heady pitch. “Devotion” (1908) has a dreamy Symbolist air, as a redheaded girl gazes skyward while pale, diaphanous blues, pinks, and yellows in her billowing blouse merge with the background’s cascading colors.

By now, Mondrian had joined the Dutch branch of The Theosophical Society. In particular, he had internalized theosophy’s hermetic quest to make visible those embedded truths that defy direct observation and empiricism. Two engrossing self-portraits in charcoal and crayon capture this newfound mysticism. In these shadowy renderings, the artist resembles a bearded, long-haired hippie 60 years ahead of the Summer of Love. His large, dark, hyper-vigilant eyes stare back at the viewer, as if to communicate a heightened consciousness.

Piet Mondrian, “Composition with Large Red Plane, Yellow, Black, Gray, and Blue” (1921), oil on canvas, 59.5 x 59.5 cm; © Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Netherlands

The theosophical quest translated into direct experiments with pure form, as it did with Hilma af Klint, 10 years his senior and precursor in abstraction. Having absorbed and tested out techniques introduced into picture-making by the Cubist and Futurist works he saw in Paris, Mondrian formulated the De Stijl school, advocating a concept called “Neoplasticism” (‘de nieuwe beelding’ in Dutch; literally ‘new art’), a principle famously defined by Mondrian as aesthetic augmentation through technical simplification:

As a pure representation of the human mind, [Neoplastic] art will express itself in an aesthetically purified, that is to say, abstract form. The new plastic idea cannot therefore, take the form of a natural or concrete representation – this new plastic idea will ignore the particulars of appearance, that is to say, natural form and color. On the contrary it should find its expression in the abstraction of form and color, that is to say, in the straight line and the clearly defined primary color.

Piet Mondrian, “Rose in a Glass” (after 1921), watercolor, crayon, and stencil ink, 27.5 x 21.5 cm; © Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, the Netherlands

The Figurative Mondrian, however, reveals that the artist did not undergo a clearly demarcated road-to-Damascus conversion from profane realism to purified abstraction. Instead, he maintained a foothold in both, with the final landscapes and still lifes in the exhibition coinciding with Mondrian’s grid paintings built on nonrepresentational lines, planes and colors.

Mondrian’s last representational paintings are as simple as they are marvelous. “A Rose in Glass” (1921) employs a captivating yellow background that seems to palpate the flower’s white petals and the translucent drinking glass from within. Structurally, the painting delineates the rhythmic indentions of the interleaving petals with a crispness that clearly articulates their triangular forms and serrated edges. This is Mondrian’s realist swan song before turning decisively to nonobjective art, spelling out nature’s core symmetries and linear formations — the same ones he would use to transform the urban grid of midtown Manhattan 20 years later, turning the fresh American cityscape into “Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1942-43).

The Figurative Mondrian continues at the Musée Marmottan Monet (2, rue Louis-Boilly, Paris, France) through January 26. The exhibition is curated by Marianne Mathieu, Scientific Director of the Musée Marmottan Monet.