He is a titan of the artworld whose work can be savage, prescient or slapstick. Ahead of a major show, the US artist looks back on studio stunts and liquid lunches with legends

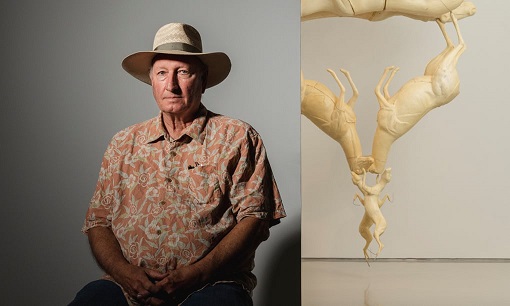

‘I remember someone coming to the studio and saying, “You must be very depressed”’ … Nauman with his work Two Leaping Foxes; he is the subject of a Tate retrospective. Photograph: George Etheredge/The Guardian

Bruce Nauman is telling me a story from his childhood. “I had a friend in high school who was a little bit of a loner,” says the artist, speaking by phone from New York. “If someone hit him with a snowball when we were walking to school, he wouldn’t just throw a snowball back, he’d attack. He’d get ’em down on the ground and pound on him.”

It is a story that seems to chime with Nauman’s art, where the line between peaceable interaction and sudden violence often seems terrifyingly thin. The artist, about to be the subject of a retrospective at London’s Tate Modern, is interested in the moment a social ritual or game pivots into cruelty. In the 1986 video work Violent Incident, a smartly dressed couple are at a table set for cocktails and dinner – but the date soon descends into a vicious brawl. You can feel pushed away by his work, alienated. “Get out of my mind, get out of this room,” urges one sculpture, via a disembodied voice that echoes round an empty space lit by a single bulb. It’s as if you’ve been sucked into the artist’s head – and it’s not a happy place to be.

The work of this 78-year-old titan of the art world, whose influence on younger artists is inescapable and pervasive, has an uncanny way of seeming forever new – and in a dark time, the work feels dark, too. The percussive rhythm of Bouncing in a Corner, No 1, a 1968 video of the artist repeatedly falling backwards into a corner of his studio, feels uncomfortably close to a metaphor for the monotonous futility of pandemic life. In 1970’s Going Around the Corner Piece with Live and Taped Monitors, the viewer catches a brief yet unsettling glimpse of their own retreating back, caught on CCTV – a premonition of the surveillance age. Then there’s Washing Hands Abnormal, his 1996 video of hands being forcefully soaped for nearly an hour. In a year when the ordinary action of handwashing has become a loaded ritual, one can’t help but feel a jolt. How did he know?

Unsettling … video work Anthro/Socio (Rinde Spinning). Photograph: Hamburger Kunsthalle/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020

I had been primed for long silences and monosyllables, but Nauman is gentle and affable, full of stories about a past peopled with the greats of postwar US culture: Jasper Johns, John Cage, Merce Cunningham. It is true that he is politely evasive about the art: for him, it seems, meaning is for the viewer to find, not for the artist to offer. When I ask about the bleakness of his work, he says: “I remember someone coming to the studio and saying, ‘You must be very depressed.’ I said that I didn’t think so, otherwise I wouldn’t be making work. A lot of things got worked out through the work. Different kinds of anger and frustration.”

It is not all dark, though: seeing Nauman’s art is to encounter a curious, questing mind, one that has restlessly experimented, over a four-decade career, with performance, film, video, sound, music, drawing, text and sculpture. Much of this inventiveness has been based on very slender means, often the materials to hand in the studio. Describing how a work might begin to take shape, he says: “Sometimes a new piece comes from work I’ve finished, maybe even quite old pieces. I begin to see a part that I hadn’t considered, that becomes more important, and that develops into an offshoot.”

A video work of his detritus-filled studio is what visitors to Tate Modern will see as soon as they enter the exhibition; the real thing is on the ranch near Santa Fe in New Mexico, where he has lived for over 30 years. The footage for the seven large projections that constitute 2001’s Mapping the Studio II with Color Shift, Flip, Flop, & Flip/Flop (Fat Chance John Cage) was gathered overnight, the equipment set running while the artist retreated. It all seems empty, eventless – but if you pay attention, you might see a cat whisk through a shot, or a flicker that might be a rat. Nauman calls it “a work that was being done while I wasn’t there”.

The only thing that was allowed … Nauman’s early film Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square. Photograph: © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020

While making it, he was also reading the journal of the 1803 expedition – led by Meriweather Lewis and William Clark – to what became the north-western US. “Every morning I would go in and replay the recording of what had been made the night before and then think about it,” he says. “It felt like this was another excursion. I was watching the studio at night and I was following Lewis and Clark. Something interesting happened to them every single day, or at least it seemed that way to me.” This is a typically oblique story of Nauman’s. What it conveys to me is the idea of the studio as, on the one hand, something familiar and everyday; and on the other, a vast and mysterious territory, full of potential incident and drama that the artist cannot control.

In the past, the studio was for the afternoons, after he’d spent the morning working with the horses he raised and bred professionally. He tells me about his friend, the trainer Ray Hunt, who “was very intuitive with the horses. He really taught you to let them figure things out on their own, not trying to be in control all the time. That adjusted the way I thought about things.” These days he doesn’t ride, but heads to the studio each morning after feeding his horses. “Usually I am just sitting reading in it with my feet up.” Then, after lunch, he says: “If I go back to the studio, I fall asleep in the chair for a while.”

Pranks … Falls, Pratfalls + Sleights of Hand (Clean Version). Photograph: © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2020

According to this account of his routine, Nauman never makes any art, which of course isn’t true. He’s still producing plenty of new work, including Nature Morte, a new 3D scan of his studio on show in his New York gallery, Sperone Westwater. Visitors can zoom in on it, invert it, investigate its corners. I wonder what he reads, though. The answer, somewhat surprisingly, is crime and thrillers, John le Carré being a favourite. It was the artist Sol LeWitt who got him on to crime fiction, he says. “The reason he liked them is – and this isn’t always the case, but it is true in Agatha Christie especially – all the information is used. You are given all the material and at some point it all locks together. There aren’t loose parts lying around.” Which is somehow perfect for the minimalist LeWitt.

Nauman’s most basic resource – his own body in the studio – has often formed material for his work. In the late 1960s, he made a group of video pieces, including the self-explanatory Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square. Their sparing form was dictated by necessity as much as anything. At the time, he was working in a studio he wasn’t allowed to leave a trace on: “No tape on the wall, no thumb tacks, no scratches, no nothing.” So he persuaded Leo Castelli, the New York gallerist, to acquire a video recorder (“Then Richard Serra used it – it got passed around”).

In recent years, he has returned to these early works, rethinking them, expanding them. In the video Walks In Walks Out (2015), he is no longer the lithe figure of the 1960s but inhabits an ageing body that has seen a great deal of life. He talks about the great US dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham. “As he got older, he couldn’t use his body as he had done 20 years previously, but he still understood how to make it function in a really interesting way – to use the edges of what he was able to do, to use that tension and make it into an artwork. That deep understanding of how his body worked – that was important for me.”

This stirs another old memory. Jasper Johns, a trailblazer for Nauman’s generation of artists, once invited Nauman and Cunningham round to his studio, to discuss Nauman designing sets, a role Johns had previously fulfilled.

“When I got there, Johns was having lunch with someone. I’d already had lunch. Being from the west coast, I’d probably had it at noon, and it was probably 1.30pm. He poured me a bourbon. Merce was late. Apparently, he poured me quite a few bourbons – because when Merce finally came in, I went to stand up and my legs just gave way from under me. I fell on my knees and hit my chin on the table. I managed to stand myself back up, and it was as though nothing had happened. We all sat back down and discussed what my role might be.”

umbles to the ground again and again. It brings to mind the very start of the show: that video of Nauman repeatedly falling into the corner of the studio. But is this it? Is this the human condition? Are we condemned endlessly, futilely, to fall? Nauman’s famous neon sculpture, the one that says “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths” will be installed at the entrance to the exhibition. As a statement, it’s hokey, ridiculous – but perhaps, on some level, true. Or is it? “I’ve never quite figured that out,” says Nauman. And he laughs.

• Bruce Nauman is at Tate Modern, London, 7 October-21 February.