정준모

William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s The Birth of Venus (1879), a print of this painting was displayed in the Arles brothel © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)/Hervé Lewandowski

Elsewhere in the manuscript Gauguin refers to the picture that he made in the Yellow House of Van Gogh in the act of painting the Sunflowers. He then quotes what Vincent apparently told him when it was completed: “It is certainly me, but me gone mad.”

Gauguin’s Vincent van Gogh painting Sunflowers (1888) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Avant et Après includes a key sentence on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers which has been widely missed because of a mistranslation. The phrase “soleils sur soleils en plein soleil” has until now been translated into English, rather meaninglessly, as “suns on suns in full sun”. But “soleils” in French can also mean “sunflowers”, so Gauguin actually meant “sunflowers on sunflowers in full sun”—a reference to Van Gogh’s still life of 15 densely packed sunflowers against a yellow background, the painting now at London’s National Gallery.

In Avant et Après Gauguin also makes the audacious claim that it was he who was responsible for Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. Gauguin writes: “I undertook the task of enlightening him… From that day my Van Gogh made astonishing progress… the result was that whole series of sunflowers on sunflowers in full sunlight” (my emphasis). The truth is rather different—Van Gogh painted his Arles Sunflowers in August 1888, two months before Gauguin’s arrival.

The English translation of Avant et Après has also occasionally been expurgated. Gauguin goes on to quote an unnamed Italian artist who was highly critical of Van Gogh’s work and his Sunflowers, but this paragraph is omitted in the English edition. The Italian is quoted as saying “mârde, mârde tout est jaune” (shit, shit everything is yellow). Gauguin deliberately misspelt the French word “merde”, presenting it as an Italian might pronounce it.

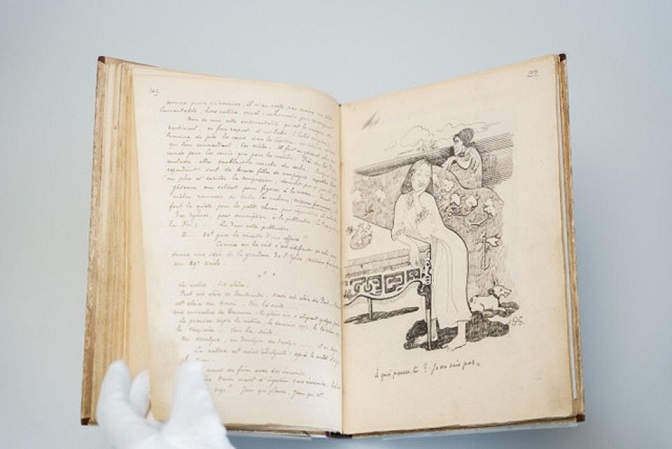

Gauguin’s account of the ear incident in Avant et Après, which starts seven lines from the top “Voici ce qui c’était passé…” (This is what had happened…) Courtesy of the Courtauld, London

But what is most fascinating in Gauguin’s manuscript is his account of the last days that he and Van Gogh had together just before Christmas 1888. Gauguin claims that a few evenings earlier they had gone to a café and Vincent had ordered an absinthe and “suddenly he threw the glass and its content toward my head”. Fortunately Gauguin avoided the blow.

On the fateful evening of 23 December Gauguin claims that he had left the Yellow House to get some fresh air, when he suddenly saw that “Vincent was rushing towards me, an open razor in his hand”. Gauguin stared at his companion, who retreated back home.

Gauguin writes in Avant et Après that he was fearful and spent the night in “a good hotel”. Although there have been some suspicions that this might have been a brothel, thanks to a long-forgotten comment by the German artist Max Braumann in 1928 we can identify it as the respectable Hotel Thévot, in the Place du Forum.

In the morning Gauguin returned to the Yellow House to discover what had happened. Van Gogh had “cut his ear close to the head” and then went “straight to a house where in every country one can find an acquaintance”, his euphemism for a brothel.

It has to be questioned whether either the absinthe glass or the razor incidents really happened—or if Gauguin presents them in Avant et Après in an attempt to justify his own actions after his friend’s self-mutilation. By 1903 Van Gogh was beginning to become famous, and Gauguin was jealous that his own reputation would soon be eclipsed by that of his Yellow House colleague.

Sorting out fact from fiction will be one of the challenges facing Gottardo and the Gauguin specialists who will be clamouring to study this long-awaited manuscript.

Martin Bailey is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019). He has written a number of bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US) and Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US). His latest book is Living with Vincent van Gogh: The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US).

• To contact Martin Bailey, please email: vangogh@theartnewspaper.com

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari